What's croaking in the pond? ¶

A new method helps to monitor endangered amphibians more quickly and effectively.

In Switzerland, 15 of the 19 amphibian species are endangered, which is an alarm signal for species conservation.

Amphibians are monitored nationwide to record their populations and distribution. However, classical monitoring is labor-intensive and not entirely reliable, as experts and trained volunteers visit ponds and count only the animals they see or hear.

Although eDNA can also be used to determine which species are present from water samples, existing methods such as DNA metabarcoding or quantitative PCR are expensive and time-consuming.

We have developed a new method: "ampliscanning", which combines eDNA with precise gene analysis using CRISPR-Dx.

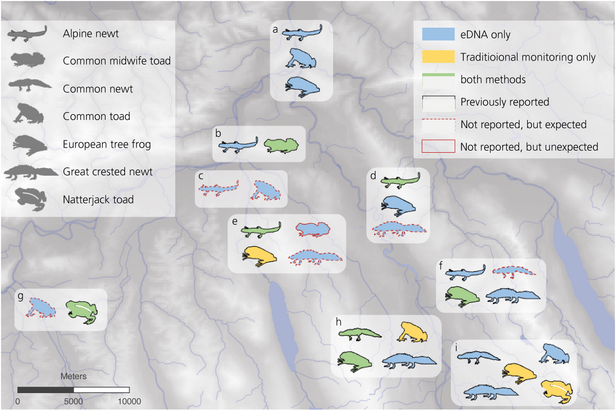

We tested the method in nine ponds in the canton of Aargau – in direct comparison with classic mapping based on visual and acoustic observations.

The following map shows how successful ampliscanning was.

More target species were discovered in a single sampling with ampliscanning than in three visits with classical monitoring.

Interestingly, ampliscanning was particularly successful with hard-to-detect species such as newts. These are easily overlooked, as they often hide in the thicket of aquatic vegetation.

Thanks to their loud calls, tree frogs were heard at two ponds where ampliscanning had not detected them. Since eDNA is not evenly distributed, it is possible that the sampled sites contained no DNA traces of tree frogs.

From the shy crested newt to the loud tree frog: these are the species we examined in our study. ¶

Innovation for species conservation ¶

Current methods of eDNA analysis reach their limits when it comes to monitoring a small group of specific species:

- Metabarcoding works well for detecting many species that occur in the same habitat at the same time. It's like investigating a crime scene without suspects: researchers analyze the DNA of all organisms to find out which species were present. However, this method is costly, time-consuming, and the results take a long time to come in.

- Quantitative PCR (qPCR), on the other hand, specializes in detecting single species. It’s like a murder investigation where you already have a suspect: scientists search specifically for the DNA of just that one species. qPCR is precise, but only provides information about one species per test.

So what if you want to detect the presence of a few target species? There is a gap between the extremes of qPCR and metabarcoding – and this is where ampliscanning comes in.