Queen of the Alps ¶

The Swiss stone pine grows mainly in the uppermost part of the forest belt of the Alps and Carpathians. A hallmark feature of these Swiss stone pine forests is the screeching call of the nutcracker. This bird collects Swiss stone pine cones and hides tens of thousands of seeds in the ground as winter food reserves.

Such small caches are often located in spots that are unsuitable for germination – so the seeds remain preserved as a food reserve. However, not all of them get eaten, so that new pines can occasionally germinate.

For regeneration, however, the Swiss stone pine requires well-developed soil. Such soil is often lacking above the tree line, which slows the tree’s spread to higher elevations.

As a result, Swiss stone pines are increasingly pressured by competing tree species pushing upward from below.

In the long term, therefore, silvicultural measures are needed to ensure that local populations do not disappear – especially at the lower edge and fringe of the species’ distribution area.

How Swiss stone pines react to environmental changes ¶

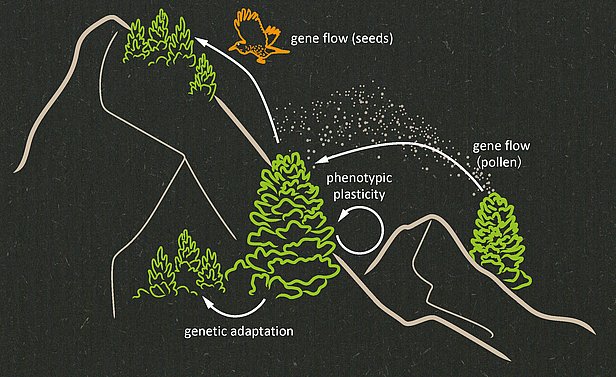

Thanks to physiological changes (phenotypic plasticity), long-lived Swiss stone pines can react to environmental changes in the short term; however, these characteristics are not inherited. Long-term, heritable adaptation is based on three processes:

- mutations randomly generate new gene variants, usually without any benefit – only rarely does an advantageous variant prevail.

- Natural selection favors gene variants from individuals with higher reproductive success.

- Gene flow through the dispersal of pollen and seeds brings gene variants into new habitats. This can be beneficial if these variants are locally adapted.

What DNA reveals about the past ¶

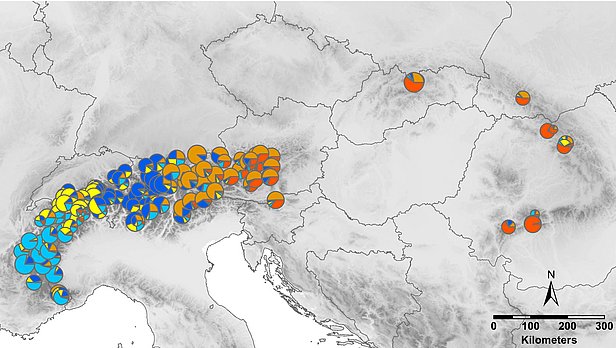

The Swiss stone pine has had to repeatedly shift its range due to climate change. During the last glacial maximum around 18,000 years ago, it survived only in a few refugia. These migrations left traces in the genetic material: our analyses of genetic fingerprints (microsatellites) show five genetic lineages of the tree species across the Alps and Carpathians.

Together with findings of pollen and plant remains, these findings allowed us to reconstruct the history of the Swiss stone pine’s expansion and retreat. Thanks to genetic patterns, we can even determine the origin of planted trees.

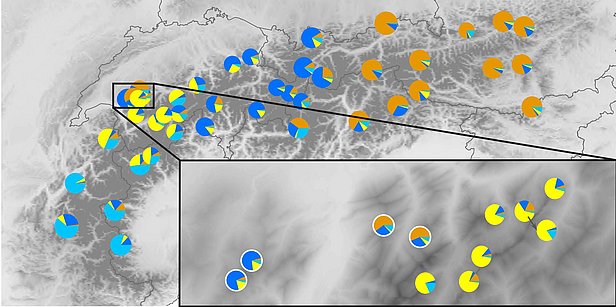

For example, where did the seeds used for large-scale reforestation in the canton of Fribourg come from? The answer can be found in the figure below.

Are Swiss stone pines ready for climate change? ¶

We wanted to know whether today’s genetic diversity of the species is sufficient for adapting to a warmer and drier climate. To find out, we sequenced the DNA of several thousand genes in over 400 old and young Swiss stone pines.

We then related the genetic differences to the climatic conditions under which the older trees had successfully competed around 160 years ago, and under which the younger trees are thriving today. The results showed that young trees near the tree line already carry gene variants that appear to be adapted to a warm, dry climate.

Such advantageous gene variants can spread through seeds and pollen. However, because Swiss stone pines have a long generation time, genetic change takes place only slowly.

Isolated Swiss stone pine populations, especially at the edge of the species’ range, will therefore likely not be able to keep pace with climate change in the long run.

Where do planted Swiss stone pines come from? ¶

The result is clear: the planted and natural populations are genetically distinct from each other. The planted Swiss stone pines did not originate from the region. Thanks to our knowledge of the genetic structure of this species in the Alps, we were able to identify the two provenances of the trees.

Meet the scientist ¶

Contact ¶

Dr. Felix Gugerli Künzle

Senior Scientist

Biodiversity and Conservation Biology

Ecological Genetics

felix.gugerli(at)wsl.ch

+41 44 739 2590

WSL Birmensdorf