Understanding how fungi spread through the air ¶

You can only protect what you know. But what if it’s barely visible?

Fungi are masters of disguise. In most species, the fruiting bodies appear only on a few days each year, and then often well hidden. No wonder, then, that there’s still so much we don’t know about them.

In Switzerland, around a third of fungal species are considered endangered. That's over 900 species! But how do you protect something that shows itself so rarely? This is exactly where eDNA helps: fungi produce countless spores, most of which are dispersed by the wind.

We capture theses spores in order to determine which species communities are present in the area using DNA metabarcoding. For example, we collect spores in traps with filter paper and can usually detect over a thousand mushroom species within just a few weeks.

This new method raises further questions that we at WSL are investigating, such as the distance over which species can still be detected.

Fungi eDNA in forest air ¶

Air pollution and climate change are altering our forests and thus also the fungal communities. But how exactly? And which environmental factors influence the occurrence of species and their fruiting body formation?

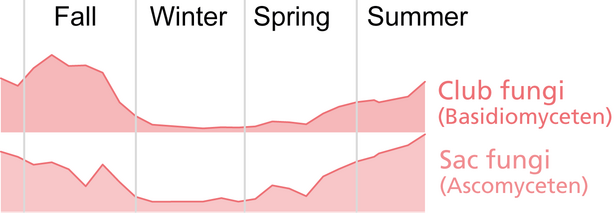

To get to the bottom of these questions, we use eDNA analysis to record fungal spores in the forest air. And we are doing so with unprecedented precision. As part of a pilot study, we collected spores from thousands of species every two weeks for a year at 15 sites of the Long-Term Forest Ecosystem Research (LWF) program. At one of these sites, we aso use an electrically powered spore trap that actively sucks in air.

In addition, we want to better understand how reliably various fungal species can be detected in the air.

Genetics for fungal protection ¶

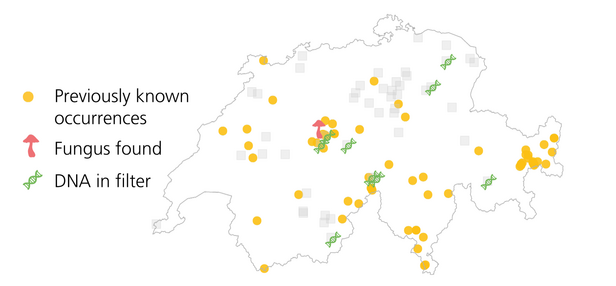

SwissFungi is the national data and information center for fungi. It documents and researches the diversity, distribution, and conservation status of fungal species in Switzerland. A large share of the data comes is collected by volunteer fungal experts. Mapping is labor-intensive.

Thanks to eDNA from spore samples, the distribution of numerous species can be recorded much more accurately. Such findings are particularly valuable for rare, endangered species such as Entoloma infula, a pinkgill species (photo and map).