Inbreeding underground ¶

Genetic analyses reveal the peculiar love life of the Burgundy truffle

The Burgundy truffle grows in Switzerland both in the wild and on plantations. We use genetic methods to explore its hidden life. This is the only way to understand how far a single fungus spreads, which individuals are related, and how new truffles are formed.

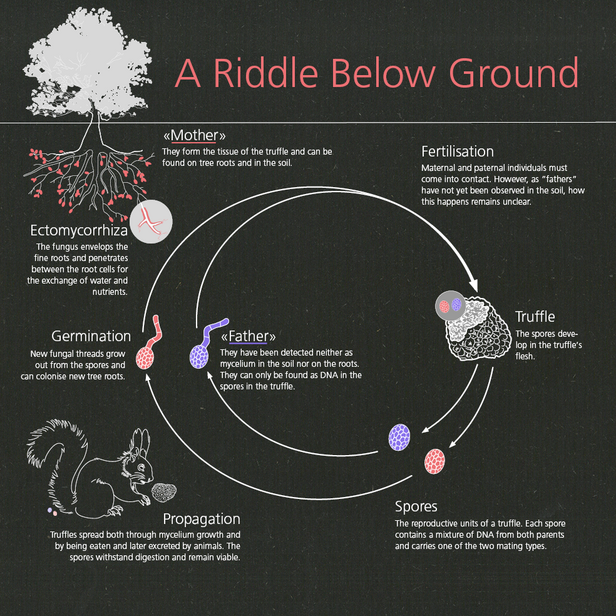

Our analyses show that there are few large truffle individuals underground – the "mothers." Over the years, they produce numerous truffle tubers. Each tuber has a different "father," yet these cannot be detected either as mycelium in the soil or on the roots of trees.

Mother and father are usually closely related. This is likely because many truffles are not dispersed by animals but instead decay in the soil. Their spores are "daughters and sons" – sons fertilize the maternal mycelium and then die.

This inbred lifestyle secures survival locally, but it carries risks: when the environment changes, there may be too little genetic diversity to allow adaptation.

Find me, eat me, spread me! ¶

The black tubers already fascinated the ancient Greeks. According to Greek mythology, truffles were created when Zeus struck an oak tree with lightning. Plutarch, on the other hand, believed they were formed by a combination of rain, lightning, and heat.

Truffles are important symbiotic partners of our forest trees, and their fruiting bodies, the prized tubers, ripen hidden in the ground. To ensure their spores are dispersed, they rely on animal helpers, such as wild boars or squirrels, which dig up and eat the truffles. To attract animals, they emit an intense scent – an open invitation to all the sharp noses in the forest.

Heat and drought threaten the truffle harvest ¶

From 2011 to 2023, the WSL conducted an observation program on the Burgundy truffle. Volunteers recorded the truffle fruiting bodies at natural truffle sites in Switzerland and southern Germany. Every three weeks, they visited the sites with their truffle dogs, dug out the truffles, weighed and described them, then sent a sample to the WSL for genetic analysis. In addition, the sites were equipped with soil sensors to record moisture level and temperature.

We evaluated these data with computer models combined with climate records. The results showed that in hot and dry years, truffle yields dropped sharply – by a quarter per degree of warming.

One finding was surprising: although Burgundy truffles also occur in very dry and hot regions such as Spain, the Central European varieties do not tolerate equally high temperatures. Apparently, truffles tend to form many small, locally adapted populations and cannot tolerate the full range of climates across their distribution area.

Our genetic analyses support this assumption: truffles tend to exchange genes only within small areas and often inbreed. As a result, southern genetic variants that might be advantageous in a warmer climate may not spread northward quickly enough – a potential disadvantage in the context of climate change.

Meet the scientist ¶

Contact ¶

Dr. Martina Peter

Group Leader

Biodiversity and Conservation Biology

Ecological Genetics

martina.peter(at)wsl.ch

+41 44 739 2288

WSL Birmensdorf