Genetic methods at WSL ¶

At WSL, we mainly use genetic methods to:

1. Identify species

- Which species are present in an area, and how are they distributed?

- Are there species that differ genetically but look the same?

- Do hybridization and backcrossing between species occur, and what is the share of each parent species in the offspring?

2. Clarify relationships

- How closely related are individuals?

- Are populations connected through gene flow?

- From which population does an individual originate?

3. Study adaptations to environmental changes

- Do populations show genetic adaptations to their environment?

- Do populations have the genetic diversity needed to adapt to future environmental conditions?

4. Measure genetic diversity

- What is the state of genetic diversity, and how is it affected by human activity?

- Are small populations at risk from inbreeding?

Here are some of the most important analyses we used in the projects on display in this exhibition – representative of many other techniques used in genetic research.

In a nutshell ¶

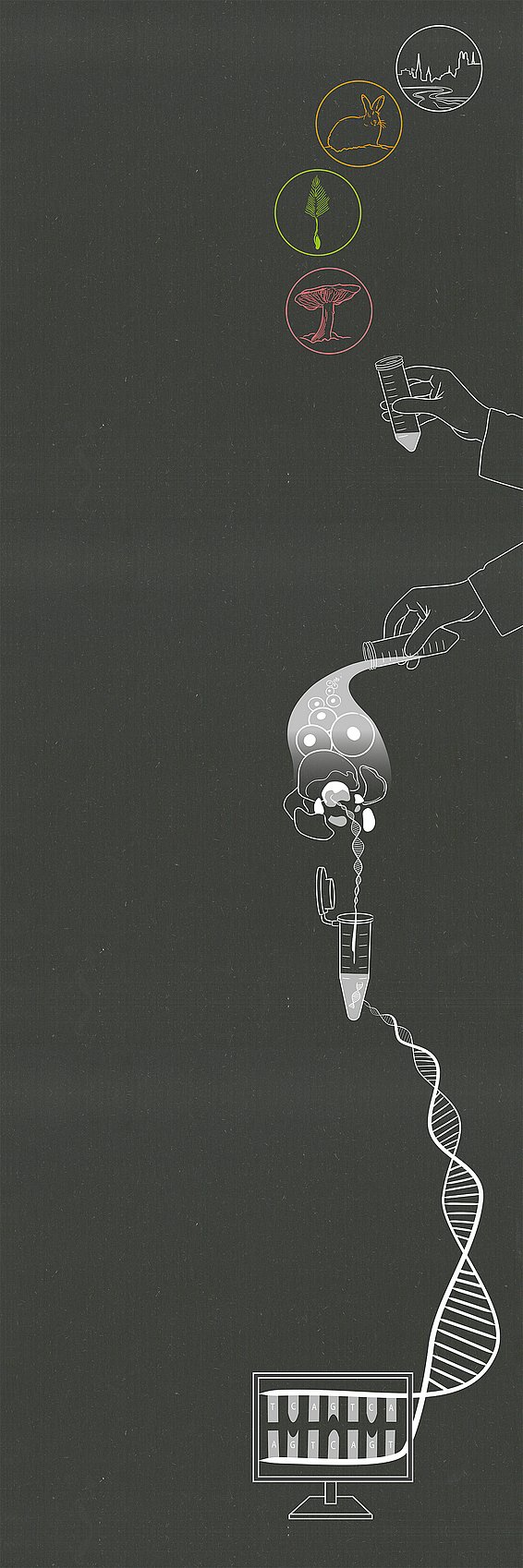

A genetic study usually involves three steps:

1. Sampling

2. DNA extraction

3. SequencingThis is followed by what is often the most time-consuming part: bioinformatics, i.e., analyzing and comparing the sequences.

Technologies have developed rapidly over the last 50 years. Costs have fallen sharply and the amount of data has increased enormously.

Genetic methods usually examine the diversity within a species – but approaches such as eDNA also make it possible to determine the species composition in a habitat.

(1) Sampling ¶

Almost anything is possible

Almost all tissues of organisms contain DNA and can be used for genetic analysis.

From blood sampling in ibexes to traps that capture fungal spores from the air: the effort involved and disruptive impact on the organisms vary significantly depending on the method.

Samples must be dried, cooled, or frozen as quickly as possible to prevent DNA from being degraded by the organism’s own enzymes.

(2) DNA extraction ¶

Getting to the core

Cells are broken down using physical, chemical, or enzymatic processes to release the DNA. All other cell components are removed as much as possible.

The aim is to obtain DNA that is as pure as possible in a solvent so that it can be used for subsequent analyses and stored long-term.

The quantity and quality of the extracted DNA are measured either optically or with the help of dyes.

(3) Sequencing ¶

DNA as a book

The type and sequence of base pairs – the DNA building blocks A, T, G, and C – are determined. This can involve reading individual base pairs or analyzing whole DNA sections. There are many methods, differing in read length (30 to 100,000 base pairs) and error rates.

Unlocking diversity ¶

Microsatellites: repetition makes the difference

Microsatellites are used in forensics, paternity testing, and population genetics – including conservation biology. They are very short, repeating sequences of up to 6 base pairs. The number of these repeating sequences often varies within or between individuals and is inherited. For genetic fingerprinting, only the length of the sequence is considered, not the actual sequence.

SNP: One letter, big impact

SNP analysis helps, for example, in assessing disease risk, identifying species, measuring genetic diversity, and evaluating adaptive potential. SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) refers to the difference at a single location in the genome where alternative base pairs are present, either within an individual or between individuals. SNPs usually have two variants, which are passed on to offspring.

Whole-genome analysis

This is the gold standard of genetic methods. It provides a comprehensive picture of an individual's genetic makeup. It can be used, for example, to measure genetic diversity and assess the adaptive potential of a species.

The DNA is broken down into pieces, sequenced, and then the sequence is reassembled like a puzzle using high-performance computers. This allows all genetic differences to be recorded – from individual base changes (SNPs) to longer sequences and even larger structural changes.