Do natural forest reserves promote the biodiversity of deadwood colonizers? ¶

Wood is a highly sought-after raw material. That is why most of our forests are intensively exploited. As a result, old trees and deadwood are becoming scarce. For many forest species, this poses a problem, since they depend on a continuous supply of old trees and deadwood in various stages of decay and of different sizes.

To counter this, natural forest reserves have been established in recent decades. In these forests, logging is prohibited, allowing natural biodiversity to re-establish itself. But is this already having an effect? And can it even be demonstrated genetically?

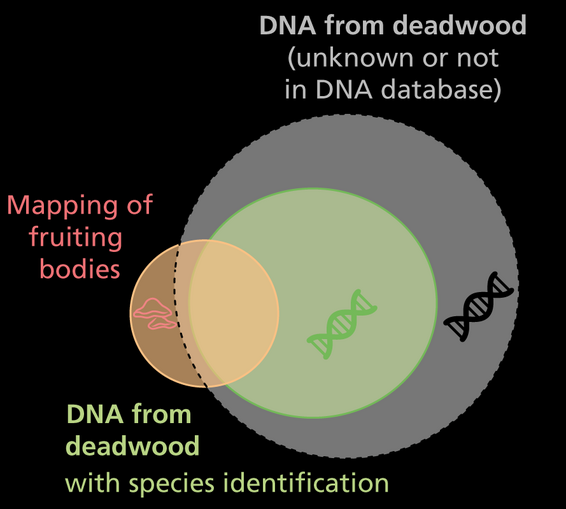

To answer these questions, we compared fungal diversity on deadwood in natural forest reserves with that in neighboring managed forests using both DNA metabarcoding and classic fruiting body mapping. This revealed interesting strengths and weaknesses of the two methods.

Surprises in genetic data ¶

When we identify fungal species based on fruiting bodies, we discover about one-third more species in forest reserves than in managed forests. However, when we determine the deadwood diversity directly through DNA analyses, we find the same number of fungal species in both forest types.

One possible reason: For the genetic analysis, we collect the same amount of deadwood in both forest types and compare the fungal diversity contained within. When searching for fruiting bodies, on the other hand, we encounter not only more deadwood in forest reserves but also a broader range of shapes, sizes, and stages of decomposition. More deadwood and a greater variety of deadwood also means more visible fungi.

What is clear: Mapping fruiting bodies shows the expected difference. The genetic method, however, reveals significantly more species regardless of forest type, including those that do not form fruiting bodies at all, or only very rarely (see graphic).

Twins on deadwood ¶

For a long time, only one species of tinder fungus was known in Europe. It was not until 2013 that the first genetic evidence emerged that there was a second species of tinder fungus in Europe.

In 2019, it was described as a separate species under the name Fomes inzengae. It is believed to be widespread in the Mediterranean region. The two species differ little morphologically – experts refer to this as cryptic species.

Our data from forest reserve monitoring now shows for the first time that both species of tinder fungus occur in Switzerland.